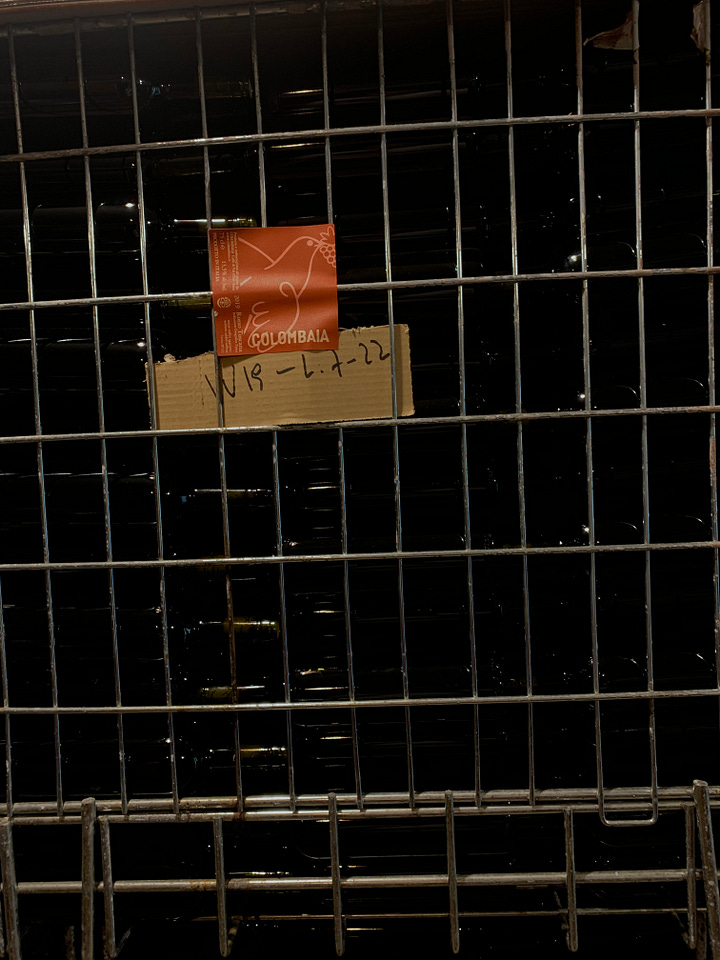

I went to Tuscany, rented a vespa, and worked half a day at a natural winery helping the owners bottle 2,000 bottles of wine all by hand. We formed a three person assembly line with the first person filling the bottles, the second pressing a button to cork the bottle (that was my job) and the third meticulously stacking the bottle in large metal pallets. As we stood there, legs cramping and our brains playing tricks on us after hours of monotonous factory movements, I couldn’t hide my fascination of the intimate connection that the owners, Helena and Dante, held to their land - and by extension each bottle of wine.

The corking machine, which Helena referred to as bastard, would occasionally fail to retrieve a cork and inconveniently halt the assembly line disrupting the flow. I on the other hand, welcomed these short errors as they offered me the only reprieve from the monotonous brain-tricking job that is solely pressing a button and picking up a bottle of wine.

It is remarkable when life altering moments arise from seemingly mundane tasks like manually corking a wine bottle for three hours. There is something extraordinary about the patience and meticulousness involved in filling, corking, and storing each bottle by hand. It is a testament to the labor invested in every step preceding it – the nurturing, harvesting, crushing, and fermenting of the grapes. Moreover, let's not overlook the profound depth of knowledge and resourcefulness required to sustain a thriving ecosystem across generations.

To encapsulate this entire process within a single bottle, allowing it to be savored, smelled, and shared, is an act of true human expression. It is a testament to the symbiosis between nature and human craftsmanship. Through this transformation, the life cycle of the vineyard expresses the collective effort and wisdom of those who dedicated themselves to its creation. It is an example of the profound connection we can forge with the world around us during a time when such relationships seem obsolete or lost.

Colombaia: a true symbiosis

Colombaia, meaning dovecot in english, is a unique ecosystem in Colle Val D’elsa, the prime growing region for Sangiovese grapes in Tuscany. It comprises a 16th century Italian villa 60 kilometers from the sea that is also a winery + vineyard owned by husband and wife, Dante and Helena. Dante inherited the estate from his father who also inherited the estate from his father and still to this day grows grapes and wine from the same vines. To describe Colombaia as solely a vineyard + winery would be a disservice as it is much more- a symbiosis of grapes, animals, vegetables, people, fungi, and fruit trees all feeding and flourishing one another.

Dante and Helena are true and genuine people who embody the undeniable fact that the relationship between the planet and humans is not a hierarchical one but rather a relationship rooted in equality, reciprocality, respect, and gratitude. To step on their property and observe its beautiful ecosystem is to understand this fact.

1 + million year old fossils

The estate is a unique ecosystem given that it has a microclimate that receives the sea breeze every late afternoon despite its location being 60 kilometers from the sea. The vines grow upon rich soil teeming with ancient fossils that add a unique minerality to the grapes (or so we say). The land that Colombaia rests upon, explained Dante, used to be the sea floor millions of years ago. When all of Tuscany was nothing but a shallow sea. As we walked through the rows of grapes each marked by various wildflowers and fruit trees, Helena would casually pick up ancient fossils sticking out of the soil like they were random pieces of rock. While indeed random, they were no ordinary rocks. They were fossils perhaps millions of years old just laying in the soil beneath our feet right at home.

“There will be a layer in the fossil record when you’ll know people were here because of the squashed remains of automobiles. It will be a very thin layer.”

- Lynn Margulis

One cannot help but feel lucky that ancient shells from an ancient long gone ocean have found their way into my hands by chance. The chance to feel and taste a microscopic blip in time compared to the eternity that these fossils are. Just as every part of the ecosystem of Colombaia has a role, so do these fossils even though they may not seem alive in the conventional sense. But they have a very important role. Their ancient minerals and hard exteriors keep the soil fresh with nutrients, they help essential fungi to navigate root systems, and they too are home to bacteria and microbes that are a thriving ecosystem in itself. It’s also sworn by some that the fossils give the wine its mineral flavor. You shall be the judge.

Spontaneous + wild fermentation

All of the wines at Colombaia use native + wild yeasts for fermentation. A wine that is wildly + spontaneously fermented uses the natural yeasts present on the skins of grapes and in the air. They do not use cultured yeasts that are grown and distributed from a lab as they often add unnecessary complexity and can be temperamental. If we took a microscope and looked at the skin of a single wine grape, we would see tens of thousands of yeast particles. All of which have the capacity to ferment the grape and produce wine if put into the right environment.

The words wild and spontaneous imply something that is natural. Untouched. unaffected. An honest expression. Natural wine growers + makers all believe in a central tenet that is - wine is a true expression of the earth, its seasons, the people who care for it, and the accumulation of their symbiotic relationships. As soon as additives, filtrations, sugars, chemicals, whatever they are- are added to wine, all of those tiny nuanced expressions are taken away. Nullified.

Predictability or spontaneity? Which do you prefer?

Cultured yeasts that are mass produced and distributed are far more consistent but lack in flavor and spontaneity that is wild fermentation. These yeasts are often used on grapes whose vines rely on chemicals, pesticides, and other manmade interventions in order to survive. Mainly because the grapes can no longer speak for themselves over years of harmful agricultural methods that reduce crucial members for a true symbiotic system. It creates a wine whose taste undeniably reflects that as the wine cannot lie. The only positive thing? The winemakers are in complete control, creating a product that can be predicted and recreated year after year.

It is like the difference between a cool, fresh fermented pickle in all its funky glory and a pickle steeped in vinegar and sugar sat on a room temperature shelf for months. Using wild yeasts present on grapes and in the air often yields inconsistent results. But it is also a result that is honest and true to the planet over a growing season. At the same time, do we really believe that harmful agricultural practices halting elements of an ecosystem’s symbiosis yields wine or anything else for that matter that is truly beneficial for us?

More on natural wine vs. conventional wine ➡️

Onward

It’s both refreshing and inspiring to know that vineyards such as Colombaia exist during a time in our planet’s history where many ecosystems lack the respect they deserve. It is testament that there is still hope for the future where an increasing number of relationships with the Earth are built upon the foundations of respect, reciprocity, and gratitude without sacrificing the progress we have made. There are vast amounts of work left to be done, but what is a more meaningful life than one that is dedicated to the earth and all its parts?

On these topics // Currently reading

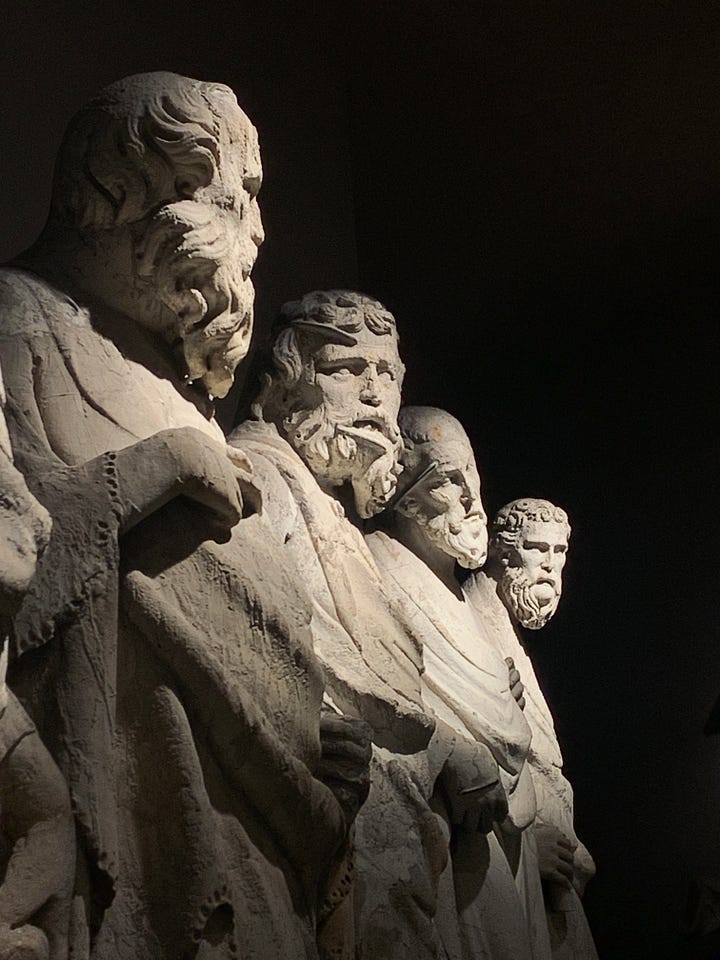

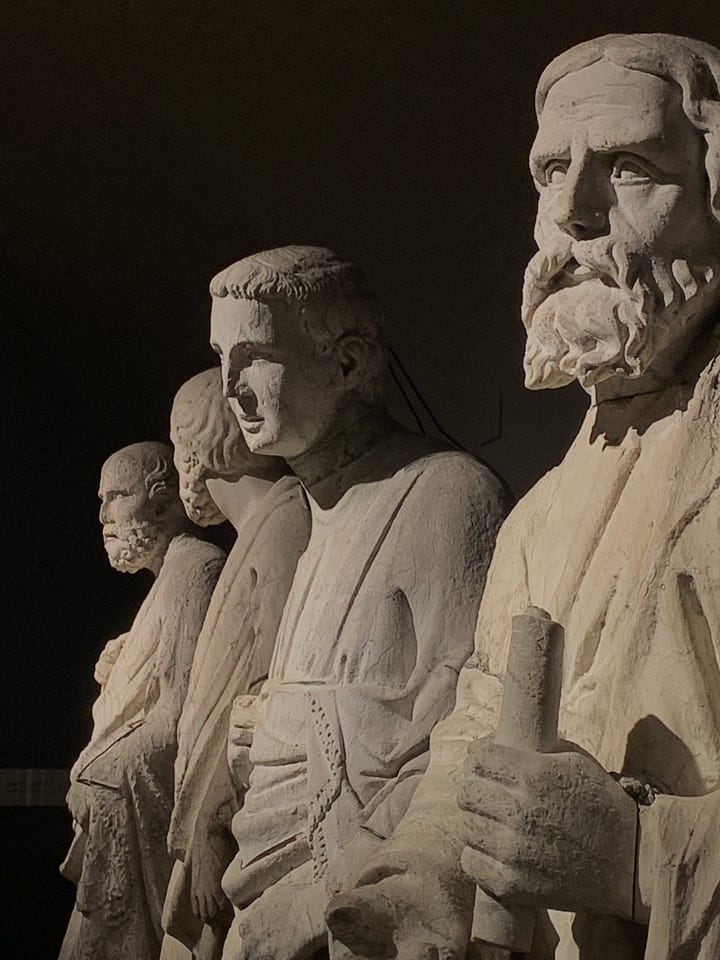

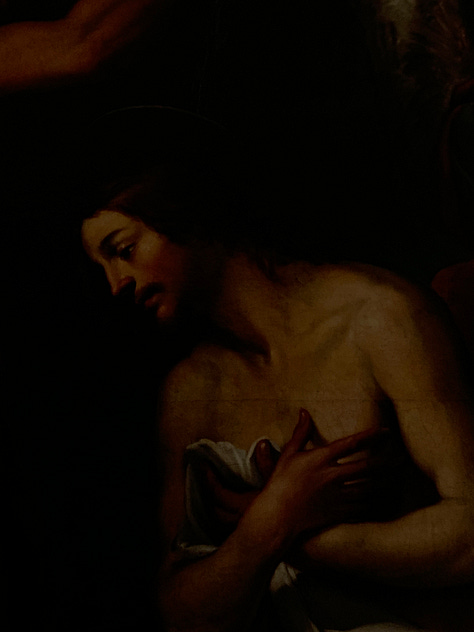

Some images from Tuscany

~Fin~